Knowledge, Evidence, and Practice

KEY POINTS

- Strong capacity is foundational to a community’s ability to act collectively, effectively govern, and sustainably manage natural resources, as well as their ability to advocate for their rights to territory and resources, assert decision making authority, negotiate with other stakeholders and/or rightsholders, access and manage funds and external support, and pursue self-determined, culturally aligned economic opportunities.

- Capacity-building strategies employ a wide range of activities that target different types of capital—including human, social, institutional, systemic, natural, and economic—which need to be tailored to the current levels of capacity and needs of the community.

- It is important to work with a community’s chosen leaders as well as within their existing knowledge systems and institutions where possible, while making special provisions for the meaningful engagement of vulnerable or underrepresented social identities (e.g., women, youth, economically disadvantaged or oppressed, ethnic minorities, etc.) in defining the rules and regulations that govern them.

- Communities can be very successful at governing common pool resources and these communities and the resources themselves often have several shared characteristics (for more on these characteristics, read on).

KEY TERMS

Capacity—multi-faceted concept generally described as “having the ability to act,” and various types of capital including human, social, institutional, natural, and economic must be used to do so.12-13

Collective Action—an action taken by a group to achieve a common objective.41-44

Common Pool Resource—any material good diminished in quantity or quality through use (i.e., subtractable) and costly or difficult to exclude others from using.45

Governance—in the context of natural resource management, refers to the norms, institutions, and processes that determine how power and responsibilities over natural resources are exercised, how decisions are made, and how people participate in and benefit from the management of natural resources.

Indigenous Knowledge—a cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs, evolving and governed by adaptive processes and handed down and across (through) generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment.46 This concept is sometimes referred to as “local knowledge” by those that do not self-identify as Indigenous Peoples.

Institutions—the rules and/or organizations that structure political, economic, and social interaction. They consist of both informal rules (e.g., sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct), and formal rules (e.g., constitutions, laws, property rights).47

Social Cohesion—a form of social capital that influences collective action; a property of a group that describes the level of connectedness and solidarity experienced by its members, which when strong can foster a sense of belonging and shared experience providing an important basis for cooperation.

Types of Capacity, Capacity-building, and Environmental Outcomes

Community-led natural resource management is a complex social process that requires collective action and effective governance of common pool resources, and is supported by investments in different types of capital (i.e., assets—both monetary and non-monetary; see Table 3). The need for strong and capable community members, leaders, and institutions makes capacity-building one of the most broadly applicable and foundational strategies of the VCA Framework. There is mounting evidence that investments in capacity-building strategies are important to environmental outcomes.48-49 Capacity is a multi-faceted concept generally described as “having the ability to act,” and various types of capital including human, social, institutional, natural, and economic must be used to do so.12-13 Capacity-building activities typically seek to enhance one or more of these forms of capital, specifically where needs are identified by a situation analysis or priorities are expressed by Indigenous and local community partners (Table 3). Though community-led natural resource management is highly context dependent,50 capacity is foundational and investments in strengthening one or more of these types of capital are almost always needed.

Table 3: Types of capital, targets of capacity-building, and some example activities. Note that it is important to consider each type of capital in any community capacity assessment (for examples on how to assess, see Hartanto et al., 2014).51

| Type of capital | Targets of capacity-building | Example Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Human |

|

|

| Social |

|

|

| Institutional |

|

|

| Natural |

|

|

| Economic |

|

|

The results of recent reviews of community-based conservation back the importance of various capacity-building investments to environmental outcomes.16 ,48 Many have identified which types of capital and commonly employed activities are most strongly associated with generating human well-being and environmental benefits. Of note are those that strengthen human capital via education, training, and technical assistance;48,52 those that strengthen social capital via efforts to build trust and increase social cohesion;16,53-54 those that strengthen institutional capital via investments in community leaders and institutions for natural resource governance;16,48,55-58 those that strengthen economic capital via investments in infrastructure, business, administration, and financial management;16 and those that build combinations of capital (e.g., human, social, and institutional) via the creation of networks for learning and knowledge exchange.16,59

Community Leadership and Institutions

See “Tool 4: Community Leaders and Institutions” for a checklist with key criteria in support of effective community leaders and institutions.

Effective community leaders and institutionsg are critical to community-led stewardship, and investments in strengthening the capacity of both have been associated with positive environmental outcomes.16,48,55-58 Leaders are essentially any individual with influence, and leadership originates from many places and can take on many forms. Community leaders can be secular or spiritual, elected or appointed, male or female, individual or collective, and can embody many qualities with bearing on environmental outcomes.60-62 In order for both community leaders and institutions to be effective at governance and have the trust and confidence of the community, they must generally be perceived as legitimate, transparent, accountable, inclusive, fair, connected, and resilient, as well as have the ability to influence peoples’ attitudes and behavior.63-64 When these key criteria are present, community leaders and institutions can be powerful advocates and motivators of collective action,65 in addition to supporting effective governance of natural resources through improved coordination, enforcement, compliance, and conflict resolution.66 Beyond this, community leaders and institutions can facilitate social learning, and the diffusion of innovations within the community and beyond.67-68 Experience has shown that when community leaders and institutions are ineffective, subject to corruption or capture of benefits by community elites, or exhibit poor coordination with others, communities often fail to uphold stewardship activities.56 Therefore, when partnering with communities to support capacity-building for community leaders and institutions, it is important to work closely with the community to identify which individuals and institutions to engage, determine what kind of training would be most welcome and helpful to complement localized knowledge and skill sets, and whether this training is likely to support stewardship goals. Working with the community’s chosen leaders and through its existing institutions is important and more likely to result in lasting positive impacts. Expect the learning to occur both ways with local leaders also having much to teach conservation organizations, in addition to what they can learn from us and others in the conservation sector.

Collective Action and Social Cohesion

See “Tool 5: Collective Action and Social Cohesion” for checklists with key resource and user group characteristics that support collective action and social cohesion.

Collective action is generally defined as an action taken by a group to achieve a common objective41-44 and is an important enabler of effective governance of common pool resources and successful community-led stewardship.69 There is a substantial body of literature that discusses the importance of social cohesion to collective action, which in turn is influenced by several resource and community characteristics, such as familiarity, frequent interaction, shared identity and purpose, reciprocity, and trust.44,70,71 These conditions are less likely to exist in communities that are large, diverse, rapidly growing or changing, involved in conflict, have pronounced inequality or legacies of oppression, marginalization, and dispossession,16,59,72-73 which are common results of colonization and subsequent intergenerational trauma. A recent analysis found community-led conservation projects that acknowledged and addressed existing trust issues (an important enabler for social cohesion) were more successful at generating human well-being and environmental benefits than those that did not.54Other studies have made related observations of the importance of shared identity and purpose to social cohesion and the collective action required for successful environmental outcomes.54 These findings argue for more awareness of the importance of social cohesion, collective action, acknowledging hard truths and lived experiences as part of trust building, and shared purpose, as well as increased investment in activities that help repair and build these fundamental conditions.

Common Pool Resources, Governance, and Sustainable Natural Resource Management

See “Tool 6: Common Pool Resource Governance” for a checklist with key conditions favoring effective common pool resource governance.

See “Tool 7: The Natural Resource Governance Tool” for step-by-step guidance on creating a context-specific governance index to assess and track governance at the community or community institution scale.

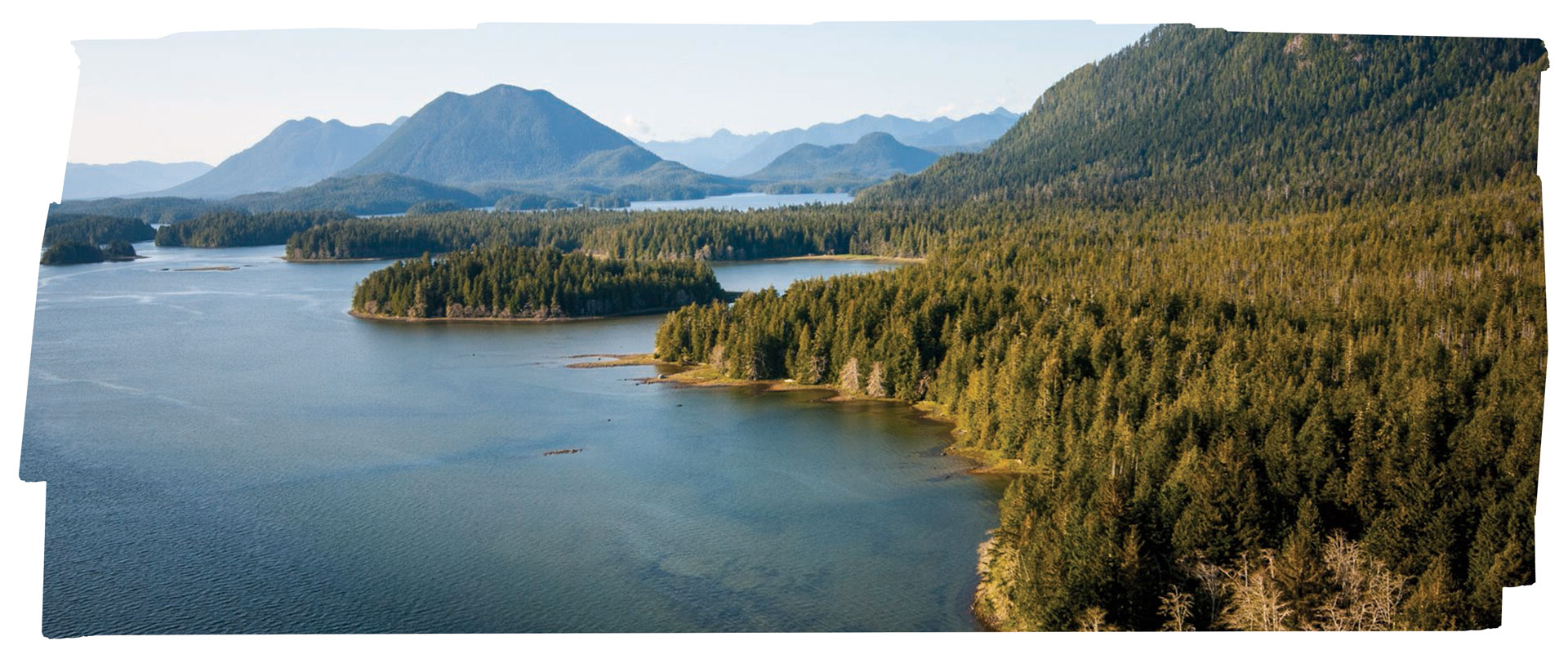

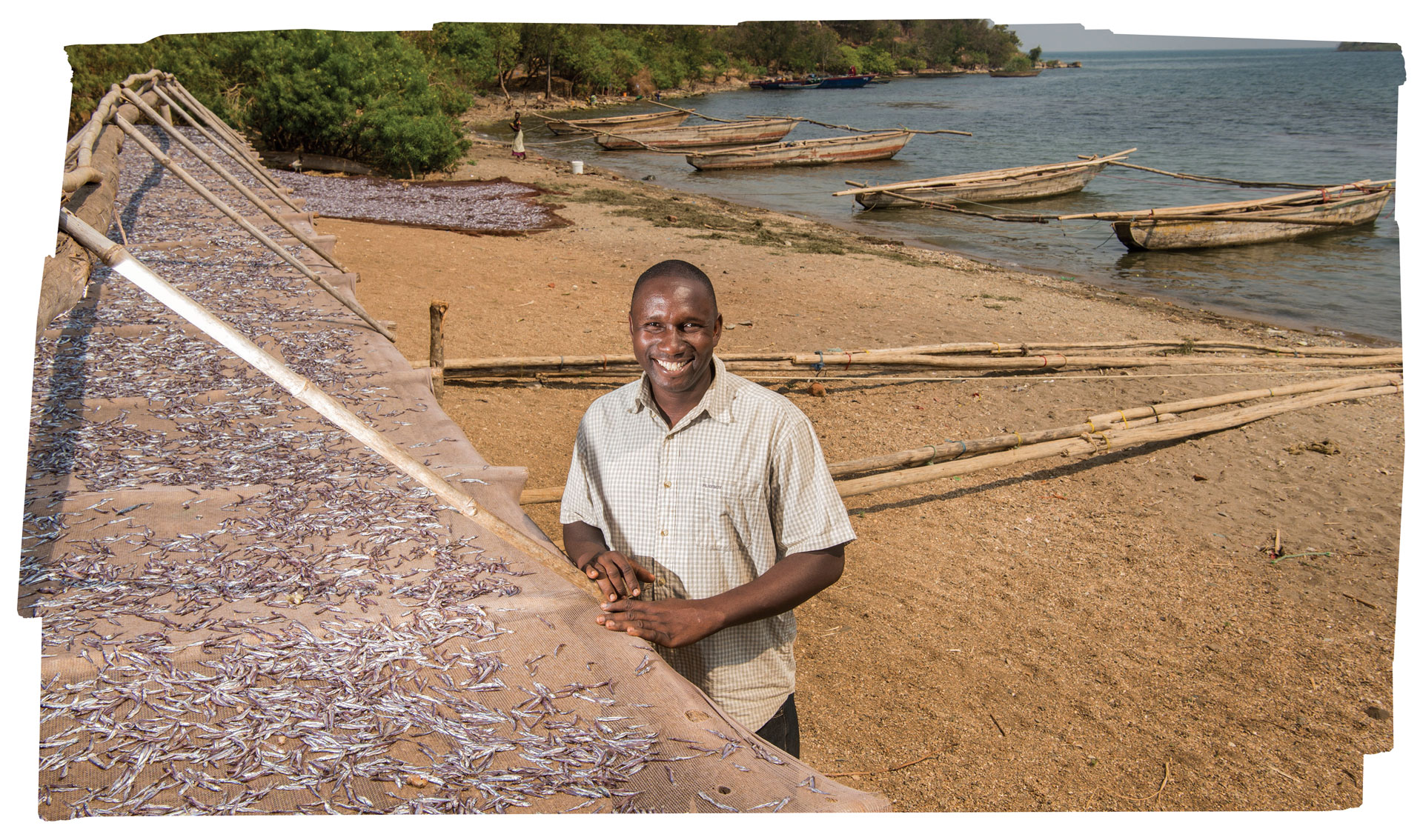

Common pool resources are any material good diminished in quantity or quality through use, and which are difficult and/or costly to exclude others from using.45 Such qualities are typical for resources that are large, heterogenous, unpredictable in space or time, and/or migratory or fugitive (i.e., moves freely between locations). Many of these resources are critical to Indigenous Peoples and local communities’ livelihoods and identities.74 Common property is a specific way of relating to common pool resources, where governance of the resource is achieved communally by a group of users with acknowledged (formal or informal; de jure or de facto) rights of access and use (see previous section for more information on property rights).75These forms of property and natural resource governance are particularly prevalent among Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

Many researchers have suggested that common property and communal resource governance is not only the optimal governance structure for common pool resources, but quite often results in more sustainable natural resource management,76-79 with studies confirming that lands and waters with long histories of governance by Indigenous Peoples and local communities (most often communal) have been well protected and sustainably managed over time.80-82 Indigenous and local community governed lands and waters see less loss of intact forest,83 more carbon storage potential,84-85 and greater provision of essential ecosystem services86 than government-run protected areas. It is important to note that while communal resource governance can result in sustainable natural resource management, this result is not guaranteed—particularly when faced with an increasing size and pace of external demand for resources. Certain conditions favor effective communal resource governance, and where these conditions are not met, failures notoriously dubbed “tragedies of the commons” can occur.87 Some of these favorable conditions include:69-70

- Resource boundaries are clearly defined,

- Rules exist for resource use that are tailored to the local context, and the benefits individuals derive from the resource are proportional to the costs,

- Those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules,

- Monitoring of resource use occurs and those that monitor are held accountable by resource users,

- Punishment for rule breakers is proportional to the severity of the offense, and

- There are quick, low cost means of resolving conflict.

For transboundary systems at larger scales, such as coasts, aquifers, rivers, or large lakes, coordination of communities and community members beyond the household or community levels becomes important for governing common pool resources. Because of interconnections among the multiple users of resources that function at larger scales, cooperation and compromises are required to ensure equitable distribution of resources and impacts. Historically, a diverse range of community-based institutions have developed, monitored, and enforced their own rules for extracting, managing, and developing such resources. Local communities can and have governed their own resources—within the limits of larger upstream/downstream or cross-boundary interlinkages—even if customary rights are not formally recognized by the government.