Foundational Element 2

Strong Connection to Knowledge and Place

Knowledge, Evidence, and Practice

KEY POINTS

- For many of the Indigenous Peoples and local communities with whom we partner, connection to knowledge and place is a critical aspect of identity and well-being, and a source of environmental reciprocity and care ethic.

- The level and intensity which humans experience connection to place can vary and change over time due to a variety of circumstances, including time spent in place, exposure to place-based knowledge, history, stories, and teachings, and ability to engage in cultural practices.

- Indigenous Knowledge and local knowledge differ from Western science, as they have often been accrued and passed on over thousands of years, and are inseparable from place, people, and the inter-relationship among them. Indigenous Knowledge continues on today in a modern, post-colonial era and is accessible to trusted knowledge keepers.

- Indigenous language, along with culture, fosters and enables environmental stewardship through carrying and contextualizing Indigenous Knowledge and instilling a worldview of respect and integration with the natural world. It entails and encodes the original instructions, spiritual and natural laws, practices, and philosophies that define connection to place.

- Any initiative that involves Indigenous Knowledge must respect intellectual property rights and data sovereignty; controlled and agreed upon access and sourcing; and center on supporting what communities decide and define as their own needs and usage agreement(s) for the knowledge shared.

KEY TERMS

Connection to Place—the relationship developed between individuals, communities, and societies and their surroundings through historical, cultural, environmental, personal, and social contexts.132

Data Sovereignty—the right to maintain, control, protect, and develop cultural heritage, knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the right to maintain, control, protect, and develop intellectual property over these.133

Indigenous Knowledge—a cumulative body of knowledge, practices, and beliefs, evolving and governed by adaptive processes and handed down and across (through) generations by cultural transmission, about the relationship of living beings (including humans) with one another and with their environment.15 This concept is sometimes referred to as “local knowledge” by those that do not self-identify as Indigenous Peoples.

Intergenerational Transfer—the passing of Indigenous and local community values, beliefs, and biocultural knowledge from one generation to the next (for example, from Elders to youth through oral narratives).134

Western Science—a system of knowledge—focused on the objective and quantifiable—which relies on application of the scientific method to phenomena in the world. The process of the scientific method begins with an observation followed by a hypothesis which is then tested. Depending on the test results (and replicability of those results), the hypothesis can become a scientific theory or “truth” about the world.

Connection to Place, Well-being, and Environmental Stewardship

Connection to place refers to the relationship developed between individuals, communities, and societies and their surroundings through historical, cultural, spiritual, environmental, personal, and social contexts.132 Places and humans’ connection to them influence culture, worldviews, and identities.135-136 Places are a social construct built from the attributes that humans observe and understand from their surroundings,137 and place attachment is an emotional bond to place that varies in intensity.138-139 Many Indigenous societies are inextricable from place, which is tied to their language, names, stories, songs, social organizational structures, knowledge, ceremonies, and spirituality. For the Indigenous Peoples and local communities with whom we partner, culture and place are often of critical importance to people’s identity and worldview, their traditional stewardship systems and use rules for lands, waters, and resources, and the conservation strategies that are most appropriate.

For many Indigenous communities, this relationship to place goes beyond provisioning into a two-way care ethic in which humans have helped foster the surrounding landscape and ecology and built continuity over time.140 For Indigenous Peoples, connection to place is often a physical feeling, as well as a psychological and socio-cultural process that has developed through ancestry, history, and responsibility. Some local communities that don’t self-identify as Indigenous who are caring for resources may also have a similarly strong connection that is related to their culture and heritage. This level of attachment reduces the ability to substitute one place for another, leads to a strong dependence on a specific place,141-143 and can result in trauma (individual and inter-generational) if people are removed from their place by force, violence, climate change, or other means.144-145 Extensive research demonstrates that a strong connection to nature and place results in stronger pro environmental behavior and conservation outcomes,141,146-147,148-156 whereas destruction of nature has negative impacts on humans both psychologically and spiritually.157 Research also indicates that the longer people live in a place, the stronger their connection.158-159

Though all humans experience place attachment, there are varying levels of intensity. Why this attachment occurs and varies relates to social organization, geography, language and cognitive structures, ritual process, rules around place use, and material production.160 This last concept—specifically a place’s ability to contribute to survival, safety, and security through provision of food, water, shelter, and livelihoods—is often the source and extent of place attachment for local communities that are newer migrants to a place and lack a culture and history that ties them to that place. For these local communities, connection is tied closely with livelihoods.161 Climate change is negatively impacting farmers’ connection to place in Western Australia. These community connections are tied to their sense of ownership and working of the land. They describe their farms as the place they live and work, whereas the literature exploring Indigenous connection does not refer to place as where they work but rather their heritage and integral part of their culture/being.162-163 There is a nostalgic relationship between the above-mentioned farming communities and their land in which they mourn deteriorating environmental conditions, and potentially deteriorating place-based attachment.162 Their connection to place distinguishes between the worked landscape and nature. This is also distinct from Indigenous understanding in which the two are intertwined.164 Additional research across diverse regions and cultures is needed to better understand local communities’ incentive to care for the landscape in a way that benefits both nature and their livelihoods.

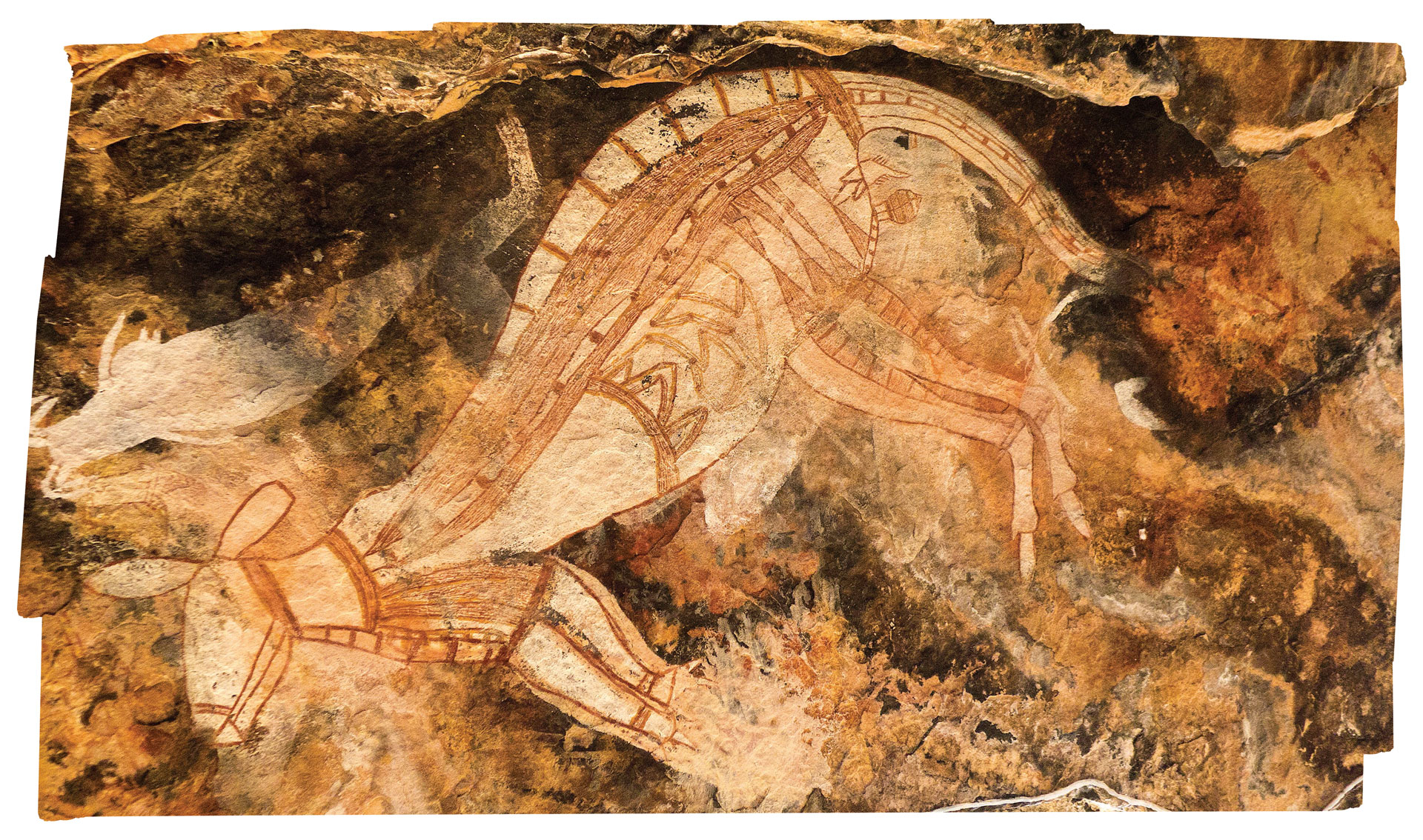

Indigenous Knowledge, Local Knowledge, and Two-Eyed Seeing (as described by Elder Dr. Albert Marshall)

The relationship between people, place, and their understanding and use of the surrounding resources is referred to as Indigenous Knowledge by those who self-identify as Indigenous Peoples, and local knowledge by those who do not. Indigenous Knowledge and local knowledge include practices for maintaining and enhancing the environment—lands, waters, flora, and fauna—and are integral to a community’s culture and livelihoods.165-167 In this worldview, culture is intermingled with place and social-ecological systems rather than separate as often seen in ecosystem services frameworks, and Indigenous Knowledge and local knowledge inform natural resource management. For example, they often take populations, habitats, and landscapes into consideration for harvesting and maintaining species which may result in both sustained populations and adequate resources available for local use (e.g., for medicines, food, baskets, canoes, etc.).167-168 Indigenous Knowledge includes concepts of respect, reciprocity, and the act of asking for permission, all of which are extended to nonhumans and passed down through generations.168,160

The knowledge of how to take care of place and natural resources have resulted in altered distribution and abundance of resources that has led to much of the biodiversity scientists find in Indigenous managed landscapes.169 These landscapes are not untouched places but rather actively managed through rules, stories, and customs that support abundance.169 For example, among the Tlingit in Alaska, there are rules surrounding access to sensitive seal breeding locations that encourage healthy populations over time.160 In Kenya, women in pastoralist communities have held extensive ecological knowledge related to the care of every life form, deeply aware of the interdependence between the spirit and earth, which is passed down through generations.170

For Indigenous Peoples, Native language is closely tied to both knowledge and place. This warrants further discussion, as there are inherent characteristics of many Indigenous languages that are not readily familiar to non-Native speakers and that are linked to environmental stewardship and relationships with Earth’s natural systems. Through carrying and contextualizing Indigenous Knowledge and instilling a worldview of respect and integration with the natural world, Indigenous language, along with culture, fosters and enables environmental stewardship. Indigenous language does so in the following ways:

- Indigenous Knowledge or reciprocity embedded in the names of species, natural resources, places, and oral history classification systems,

- Concepts of stewardship or natural resource management (caretaking) which have no direct translation in other languages,

- Linguistic structures that establish reciprocity, integration, balance, and respect towards the natural world, widely from non-hierarchical lenses,

- Place-based language that connects people to their environment and accompanying responsibilities, and

- Oral traditions, stories, histories, and what many cultures term “original instructions” which contain Indigenous Knowledge and environmental ethics and morals.171

Knowledge and the power to define what counts as real knowledge lie at the epistemic core of colonialism.171 At conservation organizations, science is foundational to our conservation work, and for many years, the Western way of scientific thinking has guided most efforts. But both organizationally and individually, we are recognizing and accepting that there are many ways of knowing and understanding the natural world and that such approaches should continue to be shared and applied by cultures across the globe, as they have done for millennia. Because Indigenous Peoples have been caring for their lands and waters for thousands of years, Indigenous Knowledge offers very rich information about places at a fine granular scale, and often across long periods of time. Accordingly, international bodies of science call for the inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge as important complements to Western scientific information. While this is true, it is also incomplete. Indigenous Knowledge is not data that can be extracted and put into Western science’s frameworks. Indigenous Knowledge offers lessons in how to live in moral and sustainable ways. It offers a framework of knowledge and analysis and is inseparable from place, people, and the inter-relationship among them. Indigenous Knowledge integrates detailed empirical knowledge, material practices, ethical and spiritual responsibilities, and Indigenous values of kinship and mutual responsibility.173 Further, Indigenous Knowledge is inseparable from place and the relationships between all beings in that place.

Indigenous societies are complex. The issue of sharing Indigenous Knowledge occurs at the interface of important aspects of this complexity. Holders of Indigenous Knowledge are not simply those who have a basic acquaintance with or academic-like awareness or education of the knowledge systems their community has been guided by for millennia. Holders of Indigenous Knowledge identify themselves using their own concepts. There are traditional governance structures that existed before present-day Tribal governments that may govern sovereignty over knowledge, how knowledge is shared, and who traditional knowledge holders are.

Working with Indigenous partners to interweave Indigenous Knowledge and a Western approach to conservation takes time, respect, and a deep understanding of the challenges and risks this work can present. Because Indigenous Knowledge is alive within a place and Indigenous Peoples’ relationship to that place, we need to begin by engaging with the Indigenous Peoples of the places we work and respect their geographic intelligence and place-based wisdom. We need to understand that some knowledge is not appropriate to be shared. A good default is to assume that all information is confidential and furthermore might not fit or be appropriate to place as ‘data points’ into Western frameworks, methods, or ways of thinking. We cannot assume that we can store partner project information in our databases or necessarily make this information publicly available. Special attention and sensitivities are called for with GIS mapping and other technology uses where cyber security and other risks lie. That said, some Indigenous Peoples will welcome the opportunity to share the Indigenous names of plants and places to restore the Indigenous identity to their homelands and to keep that knowledge active and archivable. We should expect to engage knowledge holders in an ongoing and meaningful way in developing questions, research, and management plans.

Strengthening and Sustaining Connection

to Knowledge and Place

See “Tool 15: Mapping Cultural Values” for a guide on incorporating social, cultural, and biodiversity values into spatial mapping and planning.

See “Tool 16: Intellectual Property Agreement” for a customizable intellectual property agreement template for use with Indigenous and local community partners.

See “Tool 17: Intergenerational Transfer of Knowledge and Youth Engagement” for a toolkit designed to help support and strengthen land and water-based education programs for Indigenous youth.

Connection to place is not a static state of being but rather something that continually changes and develops. In the last several hundred years, there have been enormous changes to humans’ connection to place. In some cases, the deterioration of connection to knowledge and place is the result of colonization, forced and violent relocation, residential boarding schools, and propagation of monotheistic religions—in others, it is due to the slower processes of globalization, capitalism, climate change, and lack of opportunity in place.137,144,174-175 This has impacted not only connection to knowledge and place, but associated tenure security, traditional governance structures, and overall human well-being.160

If we are to own our history as conservation organizations, we must also acknowledge and inspect how conservation has contributed to this disconnection. The conservation movement has displaced Indigenous ways through forced removal in the name of protection, blocking cultural access or use of natural resources, and by ignoring and suppressing Indigenous ways of knowing while holding up European-American Western science.176-177 Conservation has historically created a sense of exclusion rather than commons (“fortress conservation”), setting people as separate from nature.178 The approach outlined in the VCA Framework provides an alternative that helps to re-establish and/or sustain connection to knowledge and place. We commit to recognizing and uplifting the role of Indigenous Peoples and local communities as stewards, recognizing that equity, Indigenous and local community leadership and power, secure rights, local knowledge, and traditional governance are essential to both well-being and shared environmental goals.

Some of the ways in which we are working to reinforce, strengthen, and revive connection to knowledge and place include accurately representing cultural values in spatial mapping and planning, improving Indigenous and local community access to, use of, and protection of sacred places, fostering intergenerational transfer of knowledge and language, and youth education. These and other examples of actions that can be taken can be found in Table 7.

Data sovereignty related to Indigenous Peoples is their right to maintain, control, protect, and develop their cultural heritage, knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions, as well as their right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over these.133 When inquiring about and supporting connection to place, and embedded Indigenous or local community knowledge, it is important to keep in mind that much of this information is sensitive intellectual property—individuals might not be comfortable sharing, and non-community members might not have the right to know this information. Care should be taken to respect and protect Indigenous and local community intellectual property and data sovereignty. This includes co-development of intellectual property agreements, respecting Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ right not to share information that they do not want to share, and prioritizing the goal of the continued existence and use of Indigenous Knowledge and local knowledge by Indigenous Peoples and local communities to perpetuate and advance their own cultures and well-being. It also includes always seeking permission and consent and review from a community before communicating a shared story about work done together, and respecting the community’s wishes if they do not want the story told (or do not want a conservation organization to tell it).

Table 7: Examples of activities to support connection to knowledge and place.

| Approach | Example Activities |

|---|---|

| Improving access to and use of lands, waters, and resources | Facilitating rematriation or access and use agreements for private or publicly held lands of cultural significance; supporting community-led approaches to protect places and species of biocultural significance |

| Facilitating place-based education, training, and learning exchange | Supporting reinvigoration of traditional lands and waters management (e.g., traditional fire, fisheries management) and skills (e.g., boat building); upholding traditional natural resource governance systems; facilitating cross-community learning exchange and interweaving communities of practice |

| Documenting Indigenous Knowledge and local knowledge | Documenting Indigenous language; documenting stories; utilizing multi-media and other technology to attract youth and future generations to invest in their own learning, knowledge (e.g., seasonal calendars, place and species names), and history;j treating oral histories as a primary source of knowledge, if/when needed with collective attribution (collective vs. individual) to knowledge holders and sources of knowledge(s) |

| Supporting intergenerational transfer of knowledge | Championing youth culture camps; supporting access to Native languages; facilitating youth/Elder connection on lands and waters; supporting revitalization of cultural practices and ceremonies |

| Interweaving Indigenous Knowledge, local knowledge, and Western science | Application of Native language for concepts, species and place names in planning and policy; facilitating inclusion of cultural values in spatial mapping and planning;k elevating Indigenous Knowledge and local knowledge as critical forms of evidence in partnership with universities and research institutions |

| Elevating respect and recognition of Indigenous and local community ways of knowing, being, and doing | Facilitating exchanges with government agencies and Western scientists to elevate Indigenous ways of knowing, resource management, and governance and foster respectful and effective collaboration; supporting Indigenous and local community participation in policy forums to share ways of knowing; codifying Indigenous and local community cultural law into contemporary law |