Foundational Element 1

Equitable Benefits, Impacts, and Inclusion

Knowledge, Evidence, and Practice

KEY POINTS

- Supporting human rights and equity is both a moral imperative and an essential precondition for sustainable conservation outcomes. For Indigenous Peoples, this includes the right to self-determination and the standard of Free, Prior, and Informed Consent.

- Equity should be examined at both the scale of the community (e.g., community to community, company, and government) as well as the scale of the individual (e.g., across social identities). In consideration of context, reflect on whether some are benefiting more than others, being impacted more than others, and being included more than others—and take actions to avoid/address as appropriate.

- Participatory situation analysis with gender and power analysis is critical for foundational understanding of what equity means in any given context, and the power dynamics that underlie and impact partnerships with communities. Any activities should be based on sound understanding of the context and rooted in support of the specific social identities’ leadership, priorities, and vision for their participation and their future.

- Rights can vary within communities and across resources, and some social identities (e.g., women, youth, new migrants) may not be afforded the same rights as others, hence the need for an equity lens. Careful consideration of who the rightsholders are within a community and how secure any given rights are is needed, as this has implications for who has a say in use and management decisions, and who receives benefits.

- In participatory processes such as leadership and management capacity-building workshops and MSD, it is particularly important to ensure equitable participation and leadership opportunities across social identities, pay attention to micro and macro power dynamics and provide capacity-building on all sides to address power imbalances, and understand and mitigate potential unintended consequences of participation for community members.

- When supporting sustainable livelihoods, the same emphasis should be placed on ensuring equity in opportunities and benefits across social identities and avoiding unintended consequences—particularly elite capture, widening existing wealth gaps, and increase of gender-based violence.

KEY TERMS

EliteCapture—implies several related, yet distinctly different situations, including domination and control of decision making processes, monopolization of public benefits and resources, and a combination of both. The concept is also used to describe situations in which political and economic elites misappropriate resources and public funds or commit acts of malfeasance.108

Equity—a multi-dimensional concept of ethical concerns and social justice based on the distribution of costs and benefits, process and participation, and recognition, underpinned by the context under consideration. Sometimes used synonymously with fairness or justice.109

Human Rights—rights inherent to all people, whatever the nationality, place of residence, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, national or ethnic origin, race, religion, language, age, ability, or any other status. We are all equally entitled to human rights without discrimination.110

Intersectionality—first coined in 1989 by professor Kimberlé Crenshaw, describes the concept that socially constructed traits do not exist in isolation from each other, but rather are interconnected and influence each other in overt and covert ways.111

Social Identity—those aspects of a person that are defined in terms of his or her group memberships (e.g., Indigenous identity, race, ethnicity, religion or belief system affiliation, nationality, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, language, education level, socioeconomic status or class, geographic location, migration or visa status).112

See “Tool 12: Conducting a Power Analysis” for a tool that explains the multi-dimensional aspects of power, and provides guidance and templates for conducting power analysis.

See “Tool 13: Human Rights Guide” for detailed guidance on implementing a human rights-based approach.

See “Tool 14: Gender Guidelines” for detailed guidance on gender equity integration in conservation projects and strategies.

In the conservation sphere, social equity can be described as having four dimensions—1) distribution of costs, responsibilities, rights, and benefits, 2) the procedure by which decisions are made and who has a voice, 3) acknowledgement and respect for the equal status of distinct identities, histories, values, and interests, and 4) the underlying social, economic, environmental, and political history and circumstances.109 At a bare minimum, conservation organizations should be committed to “first, do no harm” in the communities with whom we partner and ensure that local people do not unjustly shoulder the costs of conservation while society benefits.113-114 TNC is committed to fulfilling this baseline social safeguard requirement and to going beyond: through supporting and advancing Indigenous Peoples’ and local communities’ visions and self-determination.

This two-fold commitment—not only to do no harm, but also to build a true partnership approach centered on equity and self-determination—requires a strong understanding of the specific context. To do so, it is important to recognize communities as a diverse mix of groups and identities. Different social groups or identities (e.g., based on gender, age, socio-economic status, ethnicity, race, religion, etc.) often use natural resources in different ways, depending on their knowledge and skills, that are directly linked with their socially defined roles and responsibilities, and are impacted in different ways. For example, certain activities may shift time allocations and increase the burden of work on more vulnerable household members, such as women and children. If these potential costs and differences are not fully understood, the success of any activity is likely to be limited, and possibly with unintended consequences for some community members. In contrast, when equity considerations are incorporated into program design, implementation, and monitoring, it will ultimately result in better outcomes for both people and nature and increase the longevity of community decisions and actions. This is supported by studies that found increased women’s participation in forest and fisheries management resulted in improved resource-use rules, increased compliance, and better protected ecosystems.115-116

Co-creating respectful, equitable relationships with Indigenous Peoples and local communities takes time. Although TNC’s engagement will look different in different situations, the responsibility to center Indigenous and local community visions for the future, and honor the diversity of social identities within these groups, remains constant. Across all activities, a robust, participatory situation analysis that includes intra-community gender and power analysis is important to understanding culturally responsive ways to support community authority and capacity. For instance, assessing the distribution of benefits—both tangible (e.g., income, technology) and intangible (e.g., education, status, participation, inclusion, safety, agency)—from conservation strategies is important, as some groups may benefit more than others. This analysis can guide how to provide that support in ways that avoid backlash and the potential for identity-based discrimination or violence. The analysis must recognize and respond to power dynamics, including different realities for different social identities, and move beyond treating any social identity as a homogenous group; rather, it is imperative to recognize that one’s full identity is made up of numerous intersectionalities across different social identities.117 Facilitating targeted and effective community participation across social identities in situation analysis is important for ensuring that subsequent activities are collaboratively developed and culturally responsive, and that they do not cause unintended negative consequences, such as backlash, identity-based violence, or imposition of outside assumptions—including assumptions about what equity looks like—that may perpetuate colonial frameworks or impacts (personal correspondence, Janine Mohamed, Lowitja Institute).

Equity in Rights and Tenure

Indigenous Peoples’ fundamental right to self-determination rests on their secure rights over lands, waters, and resources. This is affirmed in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. For example, Article 25 asserts Indigenous Peoples’ right to maintain and strengthen a spiritual relationship with their lands, waters, and territories; Article 29 outlines Indigenous Peoples’ right to conservation, protection, and productive capacity of their lands or territories and resources; and Article 32 articulates Indigenous Peoples’ right to determine priorities for lands, territories, and resources use and development.3

An equitable approach to securing Indigenous and local community rights over lands, waters, and resources may include supporting policy implementation or changes that contribute to more favorable rights and equity conditions. This approach also may also involve supporting equitable tenure, use, and inheritance rights across social identities within a community. Historically, efforts to increase tenure security have often focused predominantly on resources used by men, despite there being different uses and knowledge held by women. Further, in some contexts women may not be able to own land, and if they are able to own land together with their husband, land is oftentimes inherited by male relatives if the husband passes away. This backdrop of structural inequality undermines women’s well-being and security, as well as that of their communities and the ecosystems they protect. When women have more secure rights, they improve their resilience, their incomes, food supplies for their families, and the health of the lands, waters, and natural resources they manage.118-119

Geographic location can also impact power dynamics and rights regimes. For example, in freshwater contexts, being located upstream provides certain advantages over being located downstream, and power imbalances act to either counter or reinforce these dynamics. Notably, efforts to secure tenure may also increase the risk of conflict or discontent, as assigning and clarifying rights can have a zero-sum outcome. When someone is granted property rights another person or entity may lose those rights (e.g., moving from open access small-scale fisheries to rights-based management approaches).

Equity in Leadership, Governance, and Management Capacity

Indigenous self-determination must be at the heart of efforts to support the leadership, governance, and management capacity of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.120 This includes respecting and working with community leaders and institutions, traditional and contemporary governance structures, and decision making processes, as well as honoring and applying Indigenous and local knowledge alongside and on par with Western science,121 and taking measures to protect Indigenous and local community intellectual property. No activities should take place without Indigenous Peoples’ Free, Prior and Informed Consent, which is an ongoing process that should be undertaken throughout the entire life cycle of an initiative.122 Building capacity goes both ways—staff and partner capacity also needs to be built for advancing an equitable and human rights-based approach to this work. Conservation practitioners should be open and willing to gain new insights, skills, and knowledge the more they engage, partner, and work alongside Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

When capacity-building strategies are designed and implemented, attention to inclusion, the equity of impacts and benefits, and the possibility of elite capture are important to their success. Successful capacity-building initiatives must advance equitable access (to information, tools, and opportunities), equitable participation (in trainings, meetings, and decision making processes), and equitable leadership (in planning, implementation, and monitoring). Different rightsholders and stakeholders have different experiences, preferences, and backgrounds, and informed action is required to ensure their inclusion. For example, women often steward different natural resources than men, which is important in programming around natural resource governance and management.

We support a gender equity approach. A bounty of evidence confirms that people and nature benefit when women have stronger rights, voices, and choices in natural resource management.115-116 By including all voices, we can better support the protection of the entire suite of resources that people rely on and care for. This entails including men and boys in gender analysis and gender equity-focused activities, so that together with women and girls, similarities and differences can be recognized, and solutions proposed to favor understanding, accountability, equity, and sustainability.

Examples of actions that may further equity in efforts to support strong community leadership, capacity, and governance are listed in Table 6. Please note there may be intersectionality between many of the identities listed.

Table 6: Examples of actions that can be taken to promote equity in leadership, governance, and management capacity-building for different social identities.

| Example Social Identities | Example Equity Actions |

|---|---|

| Gener | Training and financial support for women’s networks and groups; holding additional, women-facilitated trainings for women community members; providing childcare at meetings or offering accommodations or stipends for women to bring their children and/or care providers; scheduling trainings and meetings for times and places that are safe and accessible for women and do not increase their time burden, risk exposure, and workload;h facilitating learning exchanges among women from different communities; supporting women’s capacity and confidence in areas such as public speaking, negotiations, financial management, and project leadership |

| Age | Training and financial support for youth networks and groups; fostering youth participation in decision making and leadership roles; developing sustainable livelihoods opportunities with youth; supporting Elders’ participation; supporting intergenerational connections; supporting healthy leadership transitions, mentorship, and succession planning |

| Ethnicity | Conducting workshops in local language and/or providing translation services and advertising in advance; ensuring training materials are available in accessible formats and languages;i creating methods and processes to learn and share local and ethnic knowledge surfaced and revealed; providing a neutral party peacemaker or mediator if needed |

| Socio-economic status/class | Compensating community members for their participation; ensuring meetings and trainings are not held at times of day when livelihood work is required or during harvest season; supporting and sourcing local vendors and service providers for place-based gatherings or events; avoiding preferential engagement with the wealthiest and most educated community members |

Equity in MSD

Many of the equity considerations related to designing effective multi-stakeholder dialogue and decision making processes overlap with those relevant to the leadership, governance, and management capacity pillar of the VCA Framework. The historic and current context of colonization and power imbalances necessitates capacity-building of all rightsholders and stakeholders involved. Otherwise, there is a risk of the same macro power dynamics playing out within the space of the initiative. This may involve building government or private company capacity in Indigenous rights and engagement, as well as support for Indigenous and local community capacity in engaging in policy or corporate spaces. It is important to remember that while conservation organizations can be a trusted convener in these spaces, we are not without bias, and the same principles that apply to our own capacity-building in the leadership pillar apply to our capacity-building for engagement in good faith as an actor within a multi-stakeholder environment.

Power dynamics are a key consideration in the design and success of MSD, both within the communities themselves and in relation to other stakeholder groups. In many cases, lack of formal rights, lack of capacity, and lack of economic alternatives can put local communities at a comparable disadvantage when it comes to power and influence in decision making. In the case of environmental degradation, those who benefit from environmentally degrading activities are often more powerful in the current systemic context than those who are harmed by degradation, thus forcing the less powerful actors to bear the costs.123 Differences in access, influence, resources, and information are not always easily overcome, and those in power can be reluctant to relinquish control, many times using this power to dictate the form (e.g., time of day, time of year, location) and function (e.g., process) of dialogue. Insensitivity to the needs of Indigenous Peoples and local communities can further reduce their opportunities to meaningfully engage.91 In these cases, local communities could experience “token” or meaningless participation that does not lead to significant shifts in decision making authority. It is important, too, to acknowledge the rise of anti-Indigenous governments and other actors that promote violence against environmental defenders and undermine the security of lands, waters, and resources. Some actors and spaces will be unsafe for Indigenous and local community engagement, and it is critical to understand from the partners themselves in which to support their engagement and which they prefer to avoid. In all areas where multiple actors are engaged, it is important to collaboratively develop a culturally responsive, dialogue-focused conflict resolution plan.124

MSDs should support access, participation, and leadership of all stakeholders (including vulnerable or underrepresented social identities) in all discussions and decision making.125 Communities themselves have internal diversity that must be acknowledged to ensure adequate representation and participation—for example, women, Elders, and other groups who have unique perspectives and knowledge to add to the conversation. Regarding gender equity specifically, supporting connections and exchange across women’s networks and organizations may provide an important opportunity for learning, sharing, and advancement of women’s priorities.

Please refer to Table 6 for examples of actions that can be taken to promote equity in MSD spaces. In general, attention should be paid to hidden/unintended costs of participation in the MSD (e.g., lost wages, shifts in time burden), accommodating for local languages (e.g., conducting in the local language or providing simultaneous translation), the time of day and year that the MSD takes place (e.g., not during harvest or fishing season), the format of the dialogue (e.g., aligned with traditional approaches to discussion and decision making), and that the right people are included (e.g., not just wealthy elite and with respect for chosen/traditional leaders).

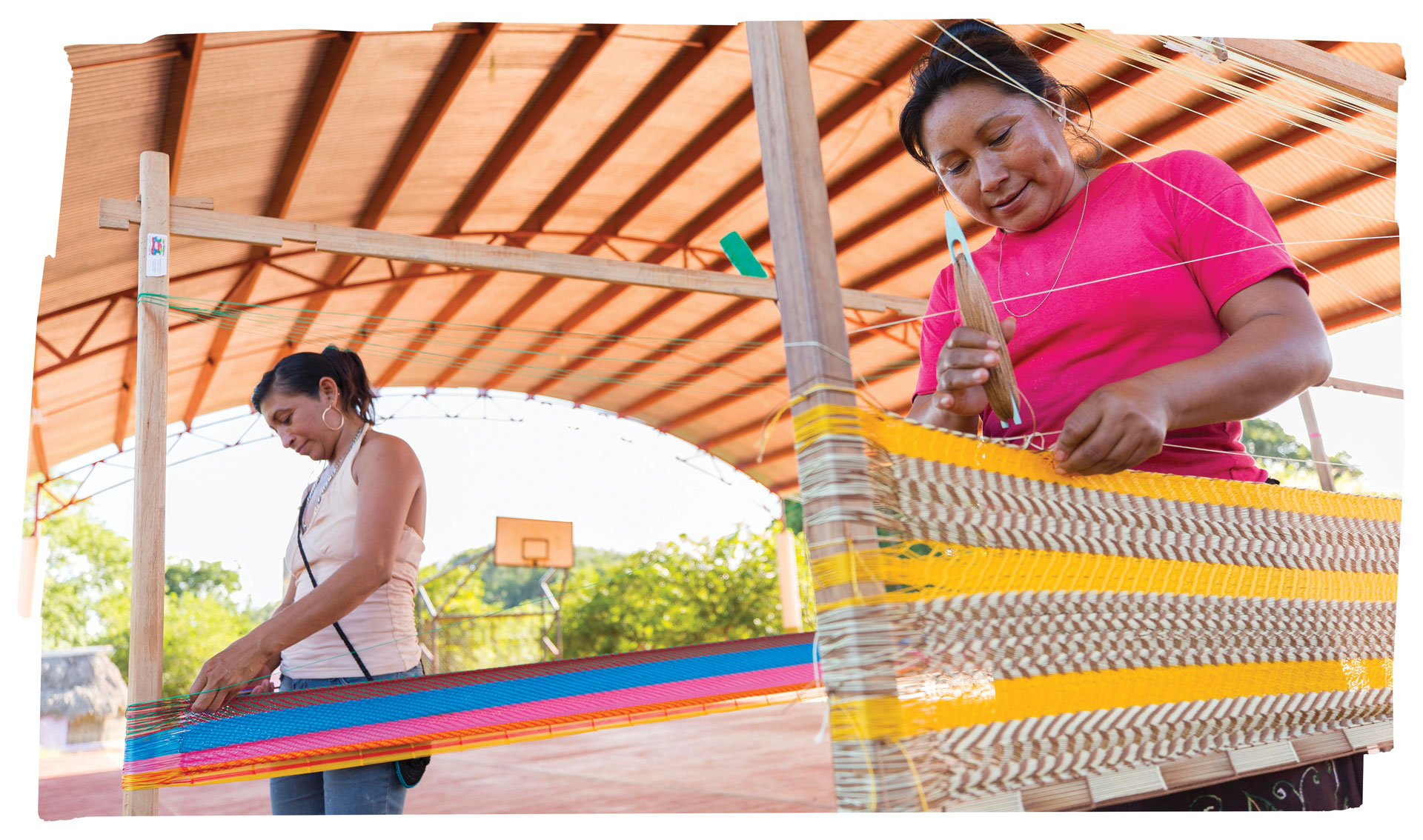

Equity in Sustainable Livelihood Opportunities

This pillar, perhaps more than any other, has the potential to exacerbate existing equity disparities, and thus great care should be taken to ensure a culturally responsive approach to equitable participation and benefit. On the other hand, sustainable livelihood opportunities have the potential to make systems more equitable, but only if these initiatives are coupled with or contribute to the transformation of current structures, which rely on inherent power imbalance. To make sustainable livelihood opportunities equitable, we must continually support the participation and leadership of different social identities in defining the “what” and the “how,” and support equitable benefit sharing within households and across social identities. Equitable distribution of benefits is also key to prevent deepening existing or creating new inequities within communities, as well as creating important co-benefits. For example, women and children may not experience benefits that are controlled by a male head-of-household. Further, if only select community members—usually the wealthiest—participate in the livelihood opportunity, income might not filter out to the rest of the community.126 Finally, it is important to identify risks and safeguard against potential unintended negative consequences, such as backlash, gender-based violence or discrimination (for example, rooted in envy, fear, or anger at the disruption of power dynamics or wealth distribution), increased time burden and workload, or exacerbation of existing wealth gaps or disparities.127-129

Examples of gender equitable initiatives focused on sustainable livelihoods include supporting women’s access to technology, assets, savings, and credits; supporting women in the production and marketing of sustainable products that come from resources that women have traditionally managed; increasing the recognition and compensation for roles that women have traditionally performed; or supporting women in new endeavors that they choose. Fundamentally, gender equity improves lives, including health outcomes,130 economic development,131 social policies, environmental sustainability, and opportunities for future generations.

Sustainable livelihood initiatives can also be critically important opportunities for youth leadership and compensation, enabling them to stay in their communities, receive knowledge passed down from their Elders, and take on roles in lands, waters, and resources stewardship. Based on an understanding of the context, targeting certain initiatives for youth participation (including both young women and young men) and intergenerational collaboration can be key for lasting positive change and a sustainable future.