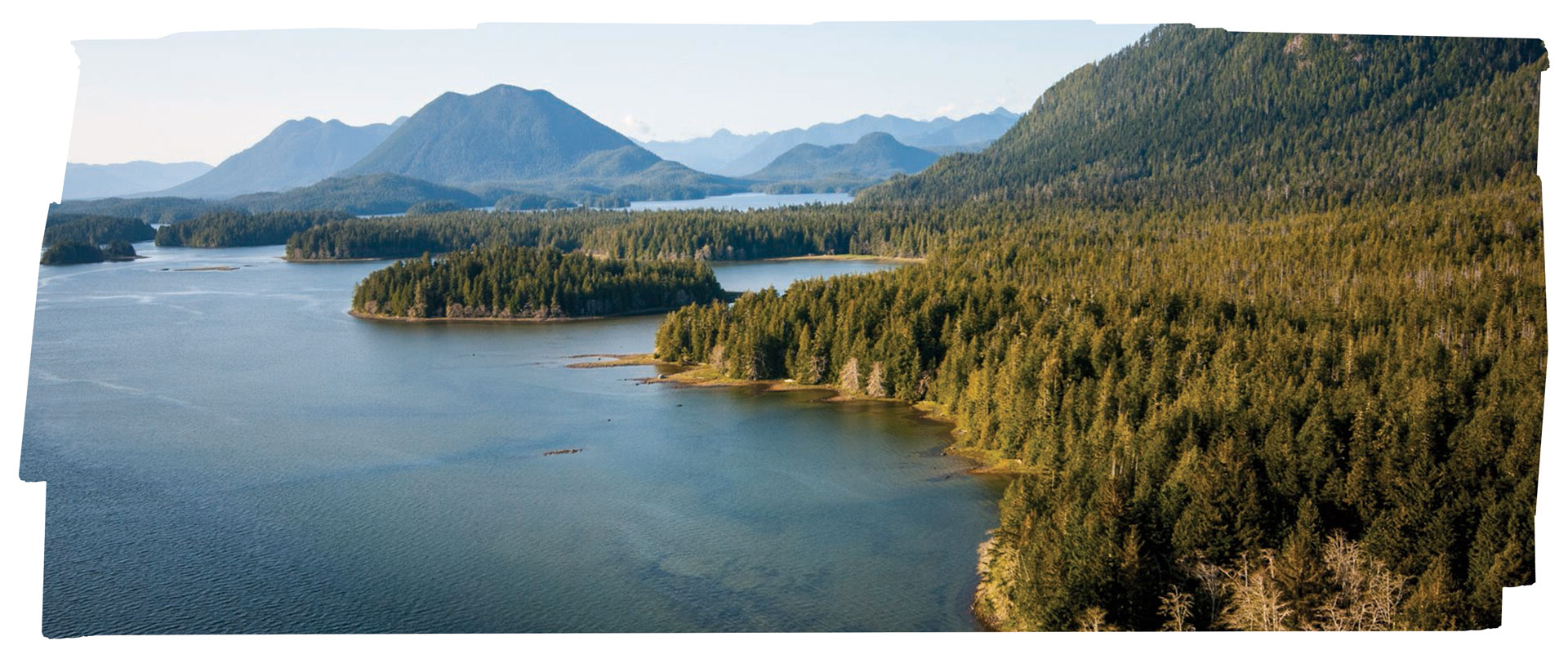

Community Leadership and Institutional Capacity-Building in the Emerald Edge

At 100 million acres (40 million hectares), the Emerald Edge is the largest intact coastal temperate rainforest system remaining in the world. This band of vibrant forest and ocean stretches northward from the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State, through Canada’s coastal British Columbia and the Great Bear Rainforest, to the panhandle of remote Southeast Alaska. Indigenous custodians have recognized rights and authority to these resources—thus the focus of the Emerald Edge Program has been on strengthening the capacity of Indigenous Peoples and local communities for continued good stewardship. TNC works to support community leadership and governance, as well as promote economic opportunities that improve local livelihoods, providing incentives and additional capacity for sustainable natural resource management.

To this end, TNC has implemented several specific programs meant to build a “ladder of opportunity” for Indigenous communities. The Supporting Emerging Aboriginal Stewards (SEAS) program—or “youth on the land programming”—aims to engage, develop, prepare, and empower Indigenous youth to become the next generation of place-based stewards. Young people take excursions onto their traditional territories to reconnect to the natural world, engage in customary activities, and learn from Elders. Another initiative, the Indigenous Guardians program, supports Indigenous rangers to take control of monitoring their territories and continue the work of their ancestors to manage and respect their natural and cultural resources through traditional institutions and governance structures. These rangers monitor the health of important food, social, and ceremonial species, taking account of various resource uses throughout their territory and contributing to the successful implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of community land and marine use plans. TNC and partners co-developed an Indigenous Guardians Toolkit to facilitate the expansion of the program within and beyond British Columbia. Building on the work in Canada, the Seacoast Trust project is establishing Guardian programs in Alaska and using both the toolkit and conservation financing endowment model to secure their vision for the future.

Expansion of this capacity-building program has continued across the Emerald Edge through the provision of critical technical and financial capacity in support of community visioning and land use planning for the Ahousaht Nation in British Columbia. A subsequent leadership exchange coordinated between the Ahousaht and Haida Nations helped Ahousaht leadership strengthen their negotiations with the Provincial Government and achieve more effective governance authority. The Ahousaht Nation also established a Coastal Guardian program, which resulted in a mapping effort in partnership with TNC (who provided technical mapping support) to delineate their territories and resources, including the integration of areas of cultural significance. All of this has served to bolster collective action, effective governance, and the Ahousahts’ negotiations with external stakeholders. For example, most recently, the Ahousaht Nation signed a new agreement with British Columbia to provide a joint set of recommendations to the Cabinet for implementation of their land use vision which will result in new conservation, forestry, and economic development areas and a governance agreement.

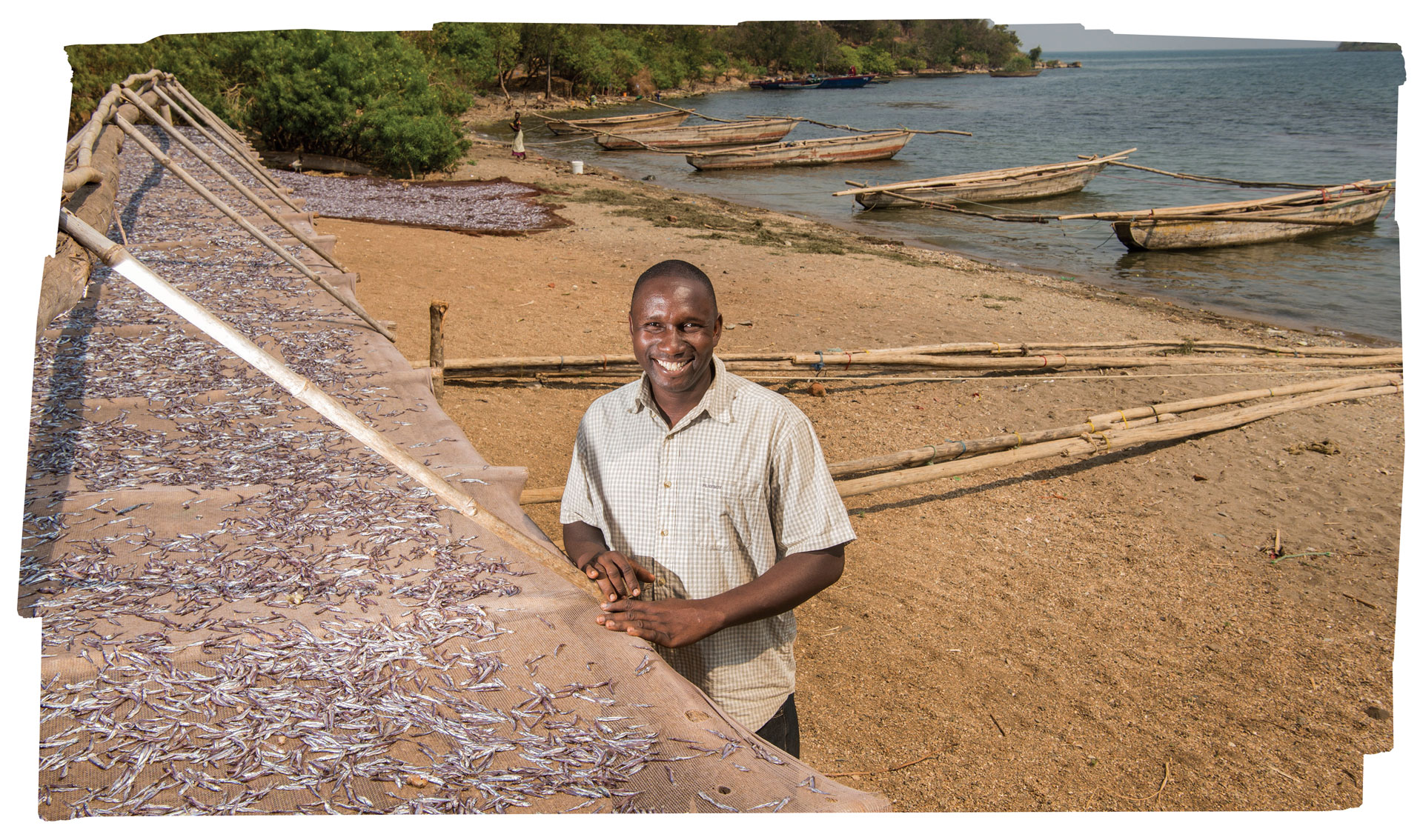

Freshwater Fisheries Management in Lake Tanganyika

For over a decade, TNC has been involved in community-based conservation initiatives and sustainable fisheries management in East Africa’s Lake Tanganyika Basin. Lake Tanganyika is the second largest lake on Earth by volume, containing 17 percent of the planet’s surface freshwater. The basin hosts some of Africa’s most iconic aquatic and terrestrial organisms and is best known for its 250+ species of cichlids, 98 percent of which are endemic. A complex web of interactions between the lake’s topography, biogeochemistry, upwelling regime, and pelagic and nearshore ecosystems has produced a productive inland fishery that supports 12 million people as a source of protein and income. Fish contributes 40 percent of animal protein in local diets, and there are an estimated 95,000 active fishers on the lake. The countries that share Lake Tanganyika—Tanzania, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, and Burundi—have varying capacity to support fisheries management, and the lake remains primarily an artisanal and subsistence open-access fishery. Additionally, the region has high population growth and high levels of poverty, exerting pressure on an already overused natural resource.

In 2012, TNC and partners established the Tuungane Project (Kiswahili for “Let’s Unite”) in Tanzania to introduce solutions that promote healthier families, fisheries, and forests, using an integrated approach that addresses both health and environmental issues simultaneously. These holistic solutions promise more durable results than the more traditional siloed approach because the conservation practices are designed to also improve people’s lives. Fisheries management under this project has focused on establishing community Beach Management Units (BMUs) to manage fisheries resources, providing BMUs with training and tools to strengthen community leadership and capacities, developing community-based monitoring systems, and creating finance mechanisms that cover the full costs of fisheries management. TNC is also seeking to actively scale impacts across Lake Tanganyika. Partnering with The Lake Tanganyika Authority (LTA)—a Lake Tanganyika regional governing body with a mandate to promote sustainable development and management of the region’s natural resources—as well as the United Nations Environment Programme, International Union for Conservation of Nature, and Global Environment Facility, TNC aims to promote fishery co-management institutions and the establishment of community-based fish reserves (protected breeding sites) across the lake.

Strong leadership and capacity are important for establishing robust institutions and coordinating action to manage common pool resources. In Tanzania, for example, village leaders are elected every 5 years. These leaders manage the community alongside an executive committee. The BMU leaders, who manage fishing resources and bylaws, are elected every three years. Leadership terms of office requires TNC to continually build relationships with new leaders and provide ongoing training to improve BMU effectiveness, income generation, and buy-in of the communities without BMUs. Terms of leadership are designed to be staggered so senior leaders will bear partial responsibility for introducing successors to the governance practices. TNC focuses on supporting more consistent and gender-equitable leadership dedicated to effectively carrying out conservation actions at the BMU level and improving BMU finance capacity. While there is a national policy in place that mandates 30% of leadership positions must be held by women (also reinforced in BMU bylaws), women in leadership positions can still be limited in their contribution and involvement due to cultural and religious norms. To address the challenges, the project facilitates purposeful nominations of female leaders, organizes tailored trainings to increase motivation and confidence, and actively engages nominated women’s partners as part of the process.

Having strong leadership in place at the village level, clear bylaws and institutional structure, the backing of the government for difficult enforcement issues, and incentives to avoid free-riders (i.e., those who benefit without paying/putting in work) have all proved critical in those BMUs that have been successful on Lake Tanganyika. Additionally, Collaborative Fisheries Management Areas (CFMAs), consisting of a confederation of BMU networks, have been created following the Tanzania guideline. CFMAs have been successful in cases where these networks can support and work with individual BMUs through wider patrols to protect relatively large areas designated as fish reserves.

However, to make the BMU financially sustainable will require a change in policy and practice that can only be made by the Government of Tanzania. TNC, in collaboration with the government and LTA, is piloting a fisheries-based business enterprises framework, the success of which will be adaptively replicated in other parts of Lake Tanganyika to enhance durable conservation of the fisheries resources. Although the Tuungane Project has had notable successes, the community-based freshwater conservation work is only starting its journey towards financial sustainability. TNC is working with partners to use value-chain analysis and harness market incentives to ensure that fishers in well-managed BMUs receive an individual and/or common financial benefit over the longer term. The first step is to advocate to the government for the return of some percentage (10-15 percent) of the government revenues (including costs for transportation of fisheries products) which is being managed by BMUs on behalf of the District Government Authority. Project success depends on effectively engaging Indigenous Peoples and local communities in an array of roles, including as land- and resource-holders, as owners and partners, and as leaders and beneficiaries. Strengthening and establishing local institutions is viewed as fundamental to long-term sustainability and resilience, and the project is increasing its efforts in this regard.