Introduction

Gratitude to and Acknowledgement of the First Stewards

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) is a conservation organization committed to creating a future in which nature and people thrive, and achieving our mission must encompass inclusion, collaboration, and supporting the original and current stewards of Earth’s natural systems. We recognize that as an organization that owns and manages land, the systems and regulations of private property, protection, and lands and waters management that have been core to our work came at a dire cost to Indigenous Peoples. With these words, we acknowledge the traditional stewards, past, present, and emerging, and recognize our institutional history, responsibility, and commitment. We are committed to gaining deeper awareness of the history and enduring impacts of colonialism—including our own contributions to this history as an organization—and resulting responsibilities, including building partnerships based on respect, equity, open dialogue, integrity, and mutual accountability.

Partner-Centered Principles

TNC’s work with Indigenous Peoples and local communities is based on building relationships, honoring self-determination, establishing trust, and focusing on shared interests. TNC’s partner-centered principles include:

- Indigenous and community-led: We seek to understand what a community wants our role to be. Together with communities, we co-create plans that align with the communities’ priorities and TNC’s experience and mission.

- Diverse and inclusive: We recognize and respect the diversity of Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and the diversity that exists within communities. We aim to center gender equity and inter-generational leadership in our work.

- Grounded in reciprocity: Our partnerships with Indigenous Peoples and local communities are opportunities for mutual learning, sharing, and benefit between the communities and TNC. We strive for transformational—not transactional—partnerships in the spirit of reciprocity.

- Based on communication and accountability: We listen deeply and open clear lines of communication. We commit to fulfilling agreed-upon roles and responsibilities, and to holding ourselves accountable for long-term partnerships and commitments.

- Flexible, adaptive, and patient: We strive to be flexible to the needs, realities, and competing priorities within communities. We recognize the interconnectedness of all things. And we learn from past mistakes.

We commit to and invite all other conservation organizations and practitioners to respect and uphold human rights standards including the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and other relevant conventions, apply and monitor social and environmental safeguards, and appropriately support the governance, knowledge systems, and self-determined sustainable visions of current and future generations of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

We commit to uphold and fully respect the distinct and differentiated rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and collaborate along shared principles and best practices to support, to the best of our abilities, the self-empowerment of Indigenous Peoples and local communities and their leadership and guidance in the inclusive and effective conservation of biodiversity, sustainable development, and mitigation of climate change.

What’s New in Version Two?

“Strong Voices, Active Choices: TNC’s Practitioner Framework to Strengthen Outcomes for People and Nature, Version 1.0” was originally co-developed and released in 2017 by a diverse group of TNC staff spanning geographies and roles, and in consideration of program experience, subject matter expertise, and scientific literature. Over the past 5 years, the framework has gained traction and been applied within the organization as our common approach to partnering with Indigenous Peoples and local communities on shared environmental and human well-being goals. The feedback has been positive, with an increase in application and usage. Since its initial writing there have been new internally and externally developed studies and analyses. These efforts, along with social and environmental changes globally, have furthered our understanding and approaches in this area. Now is the right time for a “refresh” of the framework. Readers will find much of the content from the original conservation practitioners’ document has been retained, with some adjustments and additions. These include:

- Indigenous Peoples and local community members’ review and input on framework theory and narrative, ensuring relevance of tools for advancing Indigenous and local community aspirations and visions,

- Bringing forward a holistic view of natural systems by broadening the scope of the framework and associated content, language, examples, and evidence to be inclusive of and applicable to freshwater and coastal ecosystems, in addition to terrestrial ecosystems,

- Addition of new evidence and citations, and well as tools and resources from internal and external studies and sources,

- Update and refinement of the “Tools and Resources” sections to include fewer, more actionable tools, that are of greatest use to conservation practitioners implementing the framework,

- Clearer connection between the framework and the associated common measures and TNC’s organizational metrics, and

- The formal addition of three crosscutting foundational elements that touch down in each pillar of the framework as critical enabling conditions for success:

- Equitable Benefits, Impacts, and Inclusion,

- Strong Connection to Knowledge and Place, and

- Durable Outcomes for People and Nature.

As conservation practitioners and organizations working to implement and build upon these shared concepts, now commonly known as “The Voice, Choice, and Action Framework: A Conservation Practitioner’s Guide to Indigenous and Community-Led Conservation, Version 2.0”—or VCA Framework for short—we hope you find these updates useful and that they help you advance meaningful and durable conservation work. As we collectively grow, evolve, and nurture our rights-based approaches to community-led conservation, we strive to support and strengthen the voice, choice, and action of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

An Introduction to the Voice, Choice, and Action (VCA) Framework

Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities

The VCA Framework is most applicable to people who:

- are connected to the lands, waters, and natural resources of their area or place including through strong familial ties, shared culture (e.g., language, religion, traditions, spirituality, Tribe), and shared practice ( e.g., farming, fishing, livestock keeping),

- have an inter-dependence on these systems for economic, familial, cultural, religious, and/or health and nutritional needs,

- have an interest in influencing the future health of living resources in the area,

- have historical or traditional precedents for self-governance in the area, and

- who have some level of communal or common property management over the area’s natural resources.

The people described above may lack economic opportunities, alternatives, or employment, may face significant external development pressures, may be experiencing tangible impacts from climate change that are affecting their ability to manage, steward, and use their natural resources, and may include the original inhabitants of a place and/or people who have more recently settled in a place and have a close relationship with the area’s lands, waters, and natural resources. Indigenous Peoples and Indigenous communities are communities whose members include the original inhabitants of a place and thus consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies who also inhabit the territories which the Indigenous Peoples originally occupied prior to colonization.1

Core attributes of Indigenous Peoples:

Indigenous communities, Peoples, and Nations are those which, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop, and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories and their ethnic identity as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions, and legal system (Martinez Cobo 1982). Additionally, we recognize and reaffirm that Indigenous individuals are entitled without discrimination to all human rights recognized in international law, and that Indigenous Peoples possess collective rights which are indispensable for their existence, well-being, and integral development as peoples.2

Distinctions of Local Communities:

Local communities often have a similar connection to and dependence on lands, waters, and resources for their culture and livelihoods, as well as systems of communal or common pool governance of natural resources. However, members of local communities have not collectively self-identified as Indigenous Peoples. As such, collective rights under international law available for Indigenous Peoples’ Nations may not be applicable or available to local communities. Regardless, we maintain our commitment to upholding the human rights of all local communities with whom we partner.

Indigenous Peoples (IPs) and local communities (LCs) are frequently referred to collectively as “IPLCs” in international conventions (e.g., Convention on Biological Diversity, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). We recognize the distinction between “IPs” and “LCs,” with IPs holding collective rights as enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.3 Throughout this document, we have refrained from using the acronym “IPLC” out of respect for this distinction between Indigenous Peoples and local communities, and instead spell out the full name with appropriate capitalization of “Indigenous Peoples” to recognize the diverse, sovereign communities who were living in specific regions when Europeans first attempted to name, categorize, and colonize them.

Indigenous Peoples and local communities are vital leaders in the pursuit of lasting solutions to the world’s most pressing environmental and human well-being challenges. They manage or have tenure rights over more than 25 percent of the world’s land4 and more than double that is claimed but not yet legally recognized,5 including interconnected systems of forests, grasslands, wetlands, rivers, lakes, the underlying groundwater, and coasts. With their territories harboring more than 24 percent of the world’s tropical forest carbon,6 and much of global biodiversity,7 and with nine out of 10 of the 32 million fishers worldwide being small-scale or artisanal fishers,8 Indigenous Peoples and local communities are among our most important partners, and have proven to be the most effective stewards of nature in the world—achieving greater conservation results and sustaining more biodiversity than government protected areas.9-10

Indigenous Peoples and local communities face challenges in achieving healthy and thriving communities and environments due to legacies and continued acts of colonialism, persistent inequities, and increasing consolidation of economic power. Expanding beyond this paradigm, when Indigenous Peoples and local communities’ authority and capacitya to steward their lands, waters, and resources is strengthened, when livelihood opportunities exist that are aligned with their values, and when these opportunities and benefits are distributed equitably, then durable and lasting solutions for people and nature will result. As such, we work in partnership to support natural resource management and stewardship that is defined, led, and implemented by Indigenous Peoples and local communities; grounded in community values, knowledge, and perspectives; and focused on the interconnected issues of supporting vibrant communities, strong cultures, viable local economies, and healthy ecosystems.

The People/Nature Connection

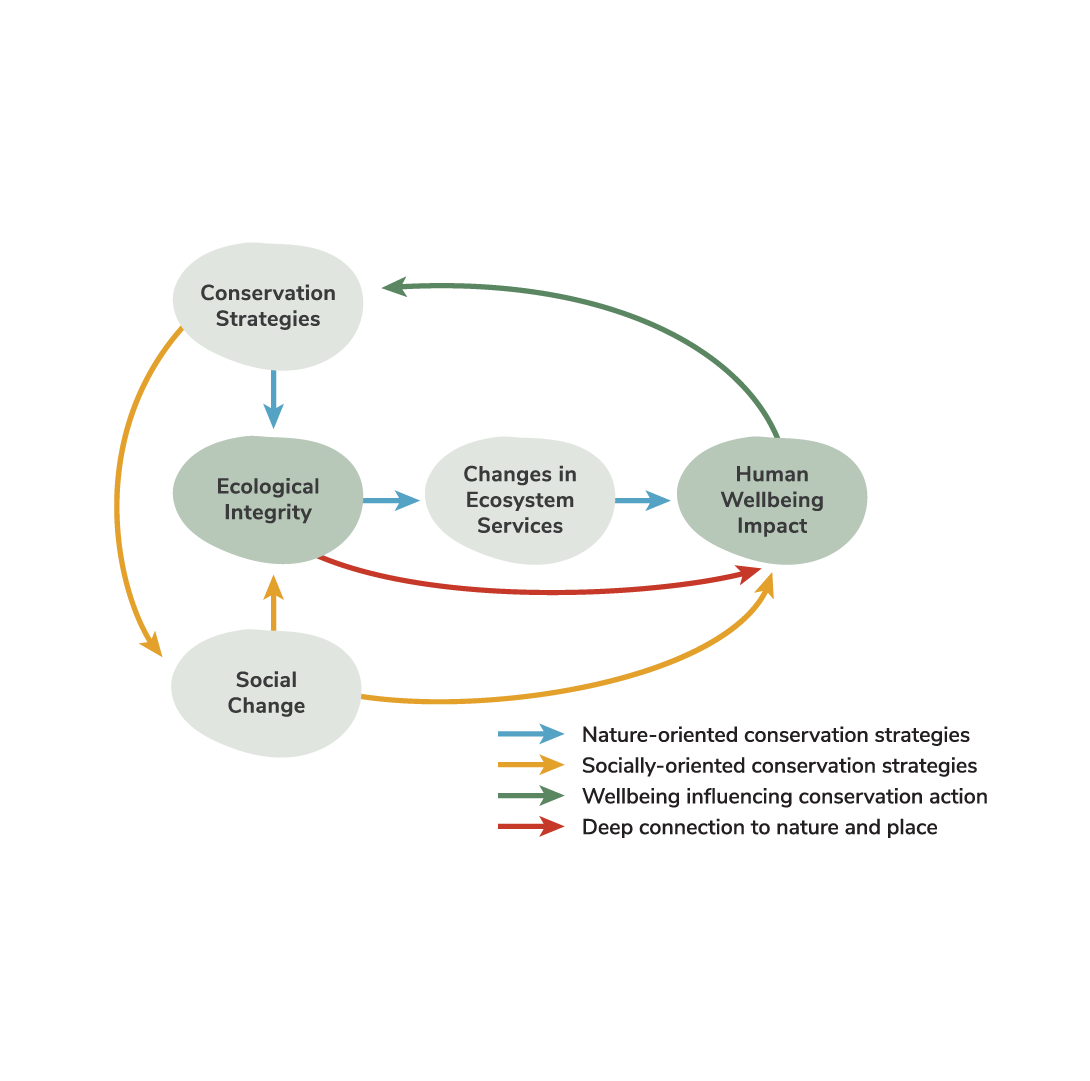

The VCA Framework is grounded in the understanding that the health of the natural world and the well-being of people are inextricably connected. This goes beyond the concept of ecosystems services (i.e., the provisioning, regulating, and supporting functions that the environment provides for people) to an integrated holistic view that incorporates the various relationships and feedback loops in the social-ecological systemb (Figure 1).

In the diagram below, the blue pathway represents one in which environmental conservation strategies lead to changes in ecosystem integrity—and subsequently ecosystem services—which then impact human well-being. This is the pathway most frequently recognized and referenced among conservation organizations. Another pathway, which is equally important in community-led conservation, is represented by the orange pathway—programs engage in socially oriented conservation strategies (e.g., capacity building, sustainable livelihoods, etc.) which lead to social change, which impact both human well-being and ecological integrity directly. At the same time, peoples’ well-being impacts their ability, capacity, and willingness to engage in stewardship actions, as depicted by the green pathway. Finally, in places where there is a deep connection to lands, waters, and resources, peoples’ perception of the health of those places may directly impact their health and identity (red pathway).

Figure 1: Diagram of the people/nature connection14

Narrative Theory of Change

Our common approach to supporting Indigenous and local community authority and capacity in natural resource management and decision making is the VCA Framework. The VCA Framework is intended for situations where human well-being and environmental outcomes are linked and interdependent, where the leadership of Indigenous Peoples and local communities is essential to achieving shared goals, where power imbalances may hinder achieving positive results for people and nature, and where projects may significantly impact local communities.

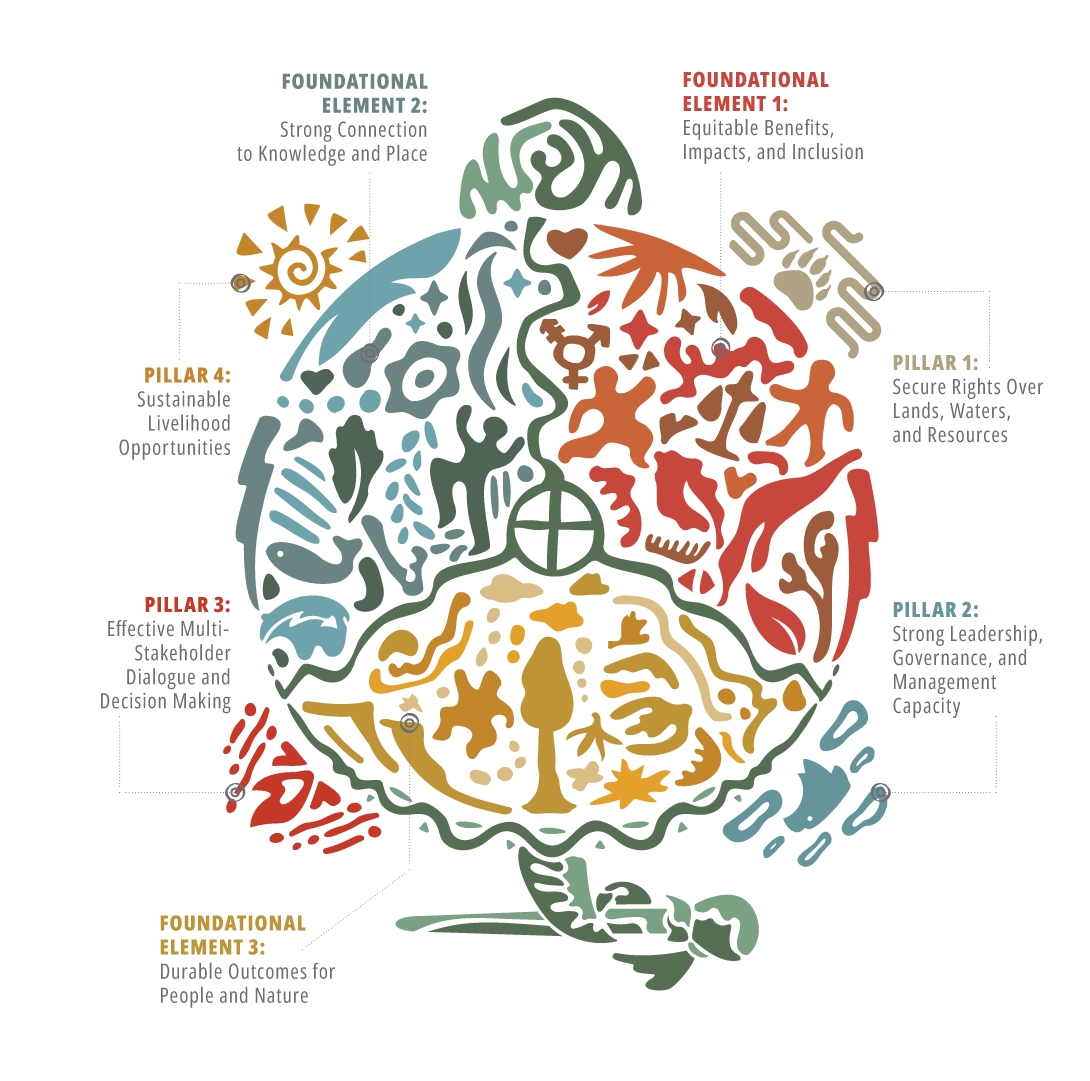

Equitable and lasting positive results for people and nature generally requires the presence of the VCA Framework’s interdependent and mutually reinforcing four pillars and three foundational elements (Figure 2). The four pillars of the framework (rights, capacity, decision making, and livelihoods) represent the characteristics necessary for successful community-led conservation. In fact, a recent systematic review and analysis suggests that as more of these four pillars are present, a higher probability of successful joint environmental and socio-economic outcomes emerges.16 The three foundational elements (equity, knowledge and place, and durability) represent enabling conditions critical for enduring community-led conservation.

Due to the interdependent nature of the VCA Framework, we do not imply an order to the pillars and foundational elements. All aspects are needed for lasting positive outcomes for people and nature, and multiple aspects are often implemented simultaneously. Further, context (e.g., existing community capacities, jurisdictional policy and institutions, ecosystem type, drivers of change, history, etc.), informed by a thorough situation analysis, will dictate which aspect(s) to prioritize in a program’s strategy.

The VCA Framework: Understanding and Putting into Practice the Pillars and Foundational Elements

This section describes the knowledge and evidence underpinning the VCA Framework, how this touches down in practice, and a small set of actionable tools and resources that have been curated as key to supporting the implementation of the VCA Framework. It begins with the four pillars, followed by the three foundational elements. The pillars of the framework (rights, capacity, decision making, and livelihoods) represent the characteristics necessary for successful community-led conservation. The foundational elements (equity, knowledge and place, and durability) represent enabling conditions critical for enduring community-led conservation. Each pillar and foundational element section includes subsections on “Knowledge, Evidence, and Practice,” “Case Studies,” and “Tools and Resources.” This information is derived from conservation practitioner and program experience, Indigenous and local community partners’ knowledge and experience, subject matter experts, and the scientific literature. The citations and references can be used in elevating and making the case for an evidence-and experience-based common strategic approach to supporting Indigenous and local community authority and capacity in natural resource management and decision making to leaders, funders, peer organizations, and partners. Conservation practitioners may find the highlighted tools and resources useful at any stage of project development—from planning and situation analysis; to implementation; to monitoring, evaluation, and learning.

We acknowledge that the evidence presented in the following sections relies heavily on Western science and can compartmentalize and simplify the complex relationships and dynamics between people and nature in specific places that create uniquely thriving and vibrant systems. Within many Indigenous and local communities, sustainability is a result of lifeways rooted in humans’ role and responsibility in maintaining the balance of all life,17 which is fundamentally at odds with the categorization that is characteristic of Western science. In our current context, we recognize that community-led conservation work still exists within societies where Western scientific thinking shapes environmental decisions and norms at micro- and macro-levels. Indigenous Knowledge and science is a whole knowledge system in and of itself, equal to all others.18 The desired outcome of providing synthesis of Western science is to support conservation practitioners who are utilizing multiple ways of knowing and working to move beyond solely relying on Western scientific teaching and practice, to expand ways of knowing that inform conservation. This section is meant to aid people who are working at this intersection, drawing on the tools of the Western system of knowledge alongside Indigenous and other ways of knowing.

Additionally, TNC is committed to a human rights-based approach to conservation, standing with Indigenous Peoples and local communities as they protect and exercise their rights. That commitment is reflected in our Vision, Values, Code of Conduct and fundamental approach to conservation, including this VCA Framework. We recognize the particular importance of Free, Prior & Informed Consent. Respecting and promoting the human rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities is both a moral obligation and an enabling condition for sustainable conservation and human well-being. For more information on our rights-based approach, see TNC’s Human Rights Guide (also discussed in the “Equitable Benefits, Impacts, and Inclusion” section).

Visual Representation of the VCA Framework

“ALL pillars and foundational elements are interconnected and interdependent, and needed for lasting positive results for people and nature”

Figure 2: Visual representation of the VCA Framework

Visual Representation Symbolism

The artwork resembles a turtle, which is a creature that thrives in all major biomes. The turtle is also a prominent part of the creation stories among many indigenous peoples. The canvas resembles a hand drum, which symbolizes the heartbeat of the universe. In many indigenous cultures, the hand drum is a sacred tool that connects heaven and earth, while also maintaining the rhythm of the world order.

The four (4) pillars are integrated in the form of the turtle’s feet. The bear’s footprint is a symbol of protection, while the Northern Lights surrounding it are symbolic of the everlasting connections with our ancestors. The eagle is widely recognized as a symbol of leadership. The fire is a symbol of a gathering place and is surrounded by dancing flames which are symbolic of people interacting in unison with one another. Finally, the sun is a symbol of life eternal, and the rays of light emanating from it represent joy, energy, and vitality.

The foundational elements are integrated in the form of representative images in three (3) distinct regions on the turtle’s back. These regions are separated by symbols of water that are connected in the middle by a sacred hoop. The sacred hoop, sometimes referred to as a medicine wheel, is a reminder that everything is related, and all things are in a continuous process of growth and progression

The turtle’s head is constructed using flowing water elements, representing life’s journey. By its very nature, the head represents wisdom, while the heart below it shows connectivity to the heart & soul.